Focus Groups according to Tremblay et al

Process description

The following activities describe the use of focus group methods to evaluate and refine design artifacts in the IS field. This method is adapted from traditional focus group techniques for use in design research projects. This method describes two types of focus groups: exploratory focus groups (EFG), which are used for the design and refinement of an artifact; and confirmatory focus groups (CFG), which are used for the confirmatory proof of an artifact’s utility in the field. The primary challenge is the structuring of focus groups so participants can collectively use an information systems artifact in order to provide feedback. This method describes one potential approach, in which participants collectively decide on an outcome both with and without the artifact, in order to compare decision-making strategies[1].

Formulate Research Problem

Description

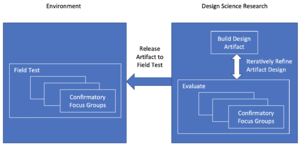

In order to effectively define the content and focus groups, the research goals must be clearly identified. Design researchers seek to design an artifact, incrementally improve the design, and evaluate its utility and efficacy. These are two complementary, yet different, research goals. The figure illustrates the positioning of the two types of focus groups—exploratory and confirmatory—in the design research process. As discussed more fully in Hevner [2007], two forms of artifact evaluation are performed in a design research project—the evaluation of the artifact to refine its design in the design science build/evaluate cycle and the field testing of the released artifact in the application environment. We discuss the similarities and differences between exploratory focus groups and confirmatory focus groups as follows[1].

Examples

Further Readings

Tremblay, Monica & Hevner, Alan & Berndt, Donald & Chatterjee, Samir. (2010). The Use of Focus Groups in Design Science Research. 10.1007/978-1-4419-5653-8_10.

Identify Sample Frame

Description

Three decisions are made in this step:

- Number of each type of focus group to run

- The desired number of participants in each group

- What type of participant to recruit

Number of focus groups

Deciding how many focus groups to run can prove to be quite challenging. The literature states that focus groups should continue until nothing new is learned[2], yet deciding ―nothing new‖ is being learned is a difficult and somewhat arbitrary task. This is especially challenging in design research. When conducting an EFG, the designers will find that there is always room for improvement of an artifact and certainly a fair amount of subjectivity in interpreting when the design of an artifact is indeed complete. There is a point where we choose to satisfice in order to move forward. For CFG, the decision that enough evidence of utility has been collected is somewhat subjective. Additionally, there is a need to balance available people and resources, since focus groups can be expensive both in terms of time and money (most participants receive some sort of compensation) and expert participants may be difficult to find. In our experience, at the minimum, one pilot focus group, two EFGs, and least two CFGs should be run. The pilot is informal (one could use students) and is used to understand timing issues and any kinks in the questioning route. A design researcher should allow for at least two design cycles and enough contrast for field test analysis. Since the unit of analysis is the focus group, it would be difficult to make a compelling argument for the utility of the designed artifact with just one CFG. In the example we outline in the later part of this manuscript, we used two CFGs.

Number of participants

Selecting group size has several considerations. It may seem simpler (and less expensive) to run fewer, larger focus groups since it takes fewer focus groups to hear from the same number of participants. Yet this could lower "sample size" since there are fewer groups to compare. Additionally, the dynamics of smaller versus larger groups are different; smaller groups require greater participation from each member, larger groups can lead to "social loafing"[3]. suggests a lower boundary of four participants and an upper boundary of twelve participants. Depending on the approach taken to demonstrate the artifact to the group (for example, whether each individual uses the artifact, versus if a moderator demonstrates it), large focus groups (more than six) could be tricky in design research since the subject matter is more complex than traditional focus group topics.

Participant recruitment

The identification of focus group participants is not a random selection, but rather is based on characteristics of the participants in relation to the artifact that is being discussed. A diversity of participants will potentially produce more creative ideas (and perhaps more conflict depending on topic), but segregation of participants based on skills and knowledge may provide more in-depth tradeoffs in values and success measures. In fact, research shows that bringing together groups which are too diverse in relationship to the topic of interests could result in data of insufficient depth[4].

For design research, the participants should be from a population familiar with the application environment for which the artifact is designed so they can adequately inform the refinement and evaluation of the artifact. Care should be taken that the participant groups are from a similar pool for both EFGs and CFGs, so that CFGs are in fact confirming a final design. Though the authors have never attempted this, an interesting approach is to use the same groups of participants twice, once to evaluate and once to confirm.

Research is mixed on whether to use pre-existing groups, though for design topics this may be advantageous since the participants have problem solved together and the focus group may approximate a realistic environment. Interaction among participants is one of the most important aspects of focus groups. For example, a group consisting of all technical experts may be very different than an expert/non-expert group[5]. A design researcher must consider membership of the focus groups and how it aligns with the research objective early in the participant selection process. For example, if the artifact is a software requirement methodology, the group membership may consist predominately of requirements analysis experts. If the artifact is a decision aid tool, a design researcher may purposely mix different skill sets: such as systems analysis, business analysis, and context experts in order to include different aspects of the aid in the conversation.

Design researchers should strive to recruit participants that are familiar with the application environment and would be potential users of the proposed artifact. Unfortunately, in many cases such individuals are not easy to find, so plenty of time and effort should be allotted for this task. For instance, it might be possible to conduct the focus group in the evening (most participants will likely work) and offer dinner. Another good approach is to conduct the focus group at a place where the potential participants work, again enticing them with lunch or breakfast. Phone calls and e-mails should be placed at least a month before the focus groups are planned. A few days before the focus groups the participants should be reminded. Researchers should plan for a few participants to not show up, so if the goal is six people, invite eight. However, care should be taken if the no-shows upset the diversity of the focus group. For example, if both medical doctors invited are no-shows, then the group may be left with no doctors.

Examples

Provide some examples for activity 2.

Further Readings

Provide further readings for activity 2.

Identify Moderator

Description

Examples

Further Readings

Develop and Pre-Test a Questioning Route

Description

Examples

Further Readings

Conduct the Focus Group

Description

Examples

Further Readings

Analyze and Interpret Data

Description

Examples

Further Readings

Report Results

Description

Examples

Further Readings

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Tremblay, Monica & Hevner, Alan & Berndt, Donald & Chatterjee, Samir. (2010). The Use of Focus Groups in Design Science Research. 10.1007/978-1-4419-5653-8_10.

- ↑ Krueger, R.A. and M.A. Casey (2000) Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 3rd edition, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Morgan, D.L. (1988) Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Bloor, M., et al. (2001) Focus Groups in Social Research, London.

- ↑ Stewart, D.W., P.N. Shamdasani, and D.W. Rook (2007) Focus Groups: Theory and Practice, 2nd edition, vol. 20, Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.